Researchers at University of Wisconsin–Madison were awarded a $2.2 million, five-year grant to study the changes that occur in the extracellular matrix — a network of molecules in which cells reside — during the development of ovarian cancer.

Their discoveries may point to potential new targets for treatment, or help to predict cancer progression or treatment responses.

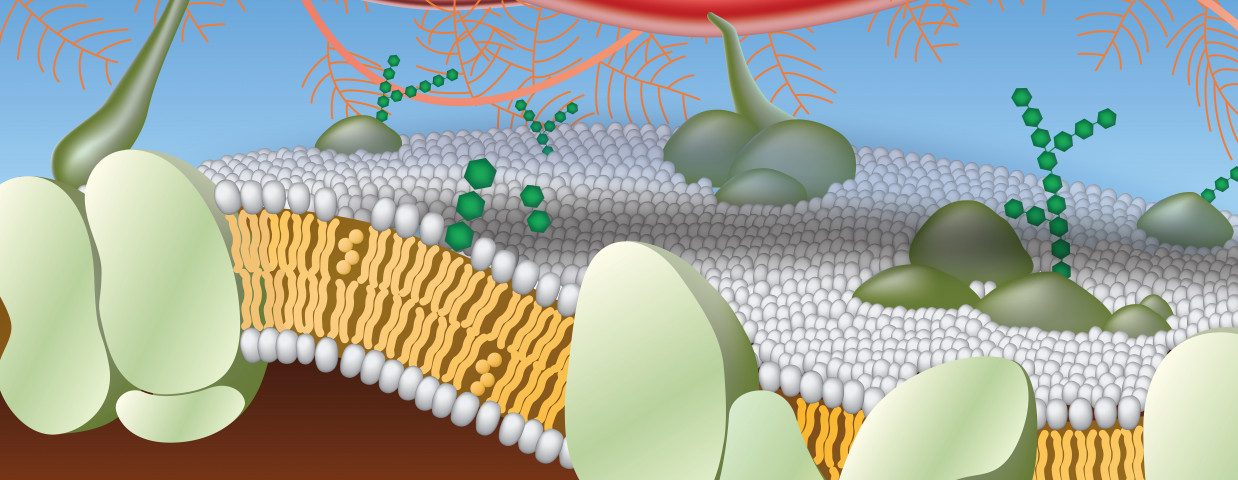

The extracellular matrix is a three-dimensional and complex network of structural proteins and other molecules that support and surround the cells of all tissues and organs. These molecules provide not only a physical scaffold, but also several biochemical signals that regulate cell function.

Problems in the structure and/or composition of this matrix are associated with the development and progression of several diseases, including cancer.

In fact, the extracellular matrix is altered in cancerous tissues, and a deregulated matrix has been shown to be a major component of the tumor microenvironment and to be involved in cancer development and progression.

However, data on the specific changes that occur during cancer development, as well as their importance, is still limited.

Biomedical engineers at University of Wisconsin–Madison plan to identify the specific changes in the extracellular matrix that occur in and drive ovarian cancer, and to develop laboratory models to study these changes in other types of cancer.

The five-year $2.2 million grant was awarded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), as a part of the Cancer Tissue Engineering Collaborative Research Program.

Researchers will analyze and modulate the extracellular matrix of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) – the most common and aggressive subtype of ovarian cancer – from its development in the fallopian tube to its spread to the ovaries and abdomen.

“Not only will we learn something about the different stages of ovarian cancer … but, more broadly, we will contribute to the goal of this NIH program by developing technologies that can then be used to study the matrix in other cancers,” Pam Kreeger, one of the project’s lead investigators, said in a press release.

Researchers will first compare the extracellular matrix between healthy and cancerous tissue (throughout the several stages of its development).

Differences in structure will be assessed through a new microscopic technique that shows in detail the physical structure of the matrix, while changes in protein composition will be assessed using mass spectrometry, which allows the identification of all the proteins present in tissue.

They then will evaluate the effects of these differences on cancer growth and migration, as well as in cancer’s chemotherapy response.

To do that, the team plans to use physical and molecular information gathered in the first phase to replicate the features of the extracellular matrix at the different stages of ovarian cancer, through two approaches.

The first approach consists in the reconstruction of this stage-specific matrix from scratch, and the second takes advantage of genetic editing to manipulate an intact tissue to produce higher levels or, or block the production of, certain proteins of the extracellular matrix.

“When you build anything from scratch in the lab, it will never look like the native tissue,” said Kristyn Masters, another lead investigator of the project.

“With this [second] approach, we can retain the richness and complexity of a native tissue, but manipulate the extracellular matrix,” she added.

Kreeger also noted that while the current best predictor of ovarian cancer progression is how much of the tumor can be removed through surgery, “if we can understand the environments of the tumors we have to leave behind, maybe we can give better outcomes for those patients.”