A research team at Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Dallas, Texas, has identified three compounds that were able to reverse resistance to chemotherapy in ovarian tumors. In lab experiments based on calculations from a supercomputer at SMU, multi-drug-resistant ovarian cancer cells died when treated with common chemotherapies and the newly identified compounds.

The discovery is important because the cells of some aggressive forms of cancer are resilient and often render chemotherapy ineffective.

The study, “Targeted inhibitors of P-glycoprotein increase chemotherapeutic-induced mortality of multidrug resistant tumor cells,” appeared in the journal Scientific Reports.

“Nature designs all cells with survival mechanisms, and cancer cells are no exception,” Pia Vogel, director of the university’s Center for Drug Discovery, Design and Delivery, and one of two senior authors of the study, said in a press release.

“So it was incredibly gratifying that we were able to identify molecules that can inhibit that mechanism in the cancer cells, thereby bolstering the effectiveness of chemotherapeutic drugs,” Vogel added.

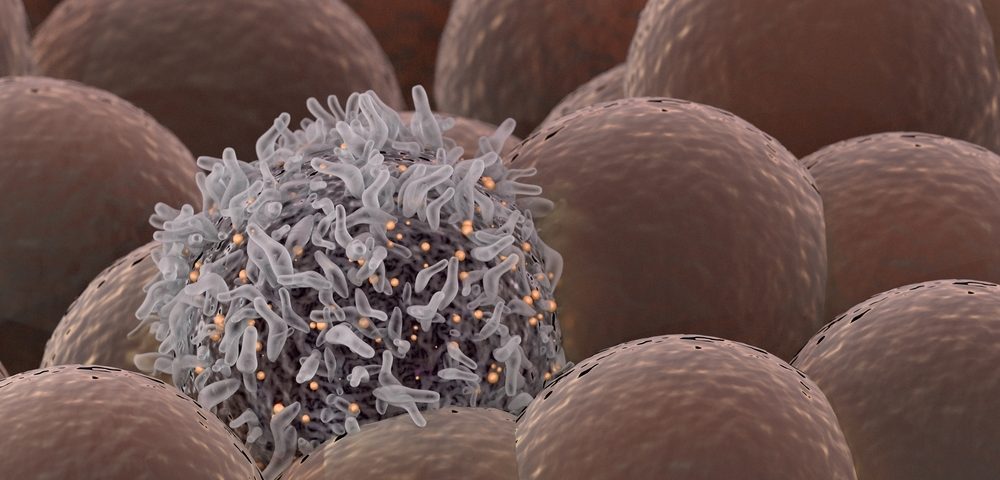

The mechanism the team explored is the most common way cancer cells become resistant to treatment. Many tumors have the ability to detect and fight off harmful substances with the help of pump proteins. These tumors react to cancer therapies, which must remain inside cells to kill a tumor, as they would with other harmful substances.

The mechanism also is present in normal cells, but tumor cells swiftly adapt to changing circumstances. When a tumor is first exposed to chemotherapy, most cells may die. Those that do survive the treatment, however, tend to maximize their production of these pump proteins, making cells resistant to further treatment.

“The cancer cell itself can use all these built-in defenses to protect it from the kinds of things we’re using to try to kill it with,” said John G. Wise, co-senior author of the study.

In a previous effort, the researchers had identified a number of compounds that could potentially counter this mechanism by using computer simulations. They tested the results of those simulations on lab-grown ovarian and prostate cancer cells that were resistant to several types of chemotherapy.

The results of their experiments showed that when these compounds were delivered with chemotherapy, the tumor cells could no longer reject the treatment. The three compounds were seen to boost the death of cancer cells and curb their ability to move, a key feature in the spread of cancer.

Interestingly, researchers found that the compounds needed to be delivered with chemotherapy, as they had no impact on cancer cell survival when delivered alone.

“We saw the drugs penetrate these resistant cancer cells and allow chemotherapy to destroy them,” Vogel said.

“We wanted to make sure when using these really aggressive cancers that if we do knock out the pump, that the chemotherapy goes in there and causes the cell to die, so it doesn’t just stop it temporarily,” Wise added.

All three compounds blocked the actions of a pump protein called P-glycoprotein, one of the most common proteins involved in chemotherapy resistance. One compound also blocked a pump protein called BCRP, which mediates resistance in breast cancer cells.

The discovery is far from leading to a market-ready therapy, and more research is needed, the scientists said. Nevertheless, Vogel said the “success in the lab gives us hope for developing new drugs to fight cancer.”